This is the Nov. 23, 2021, edition of the Wide Shot, a weekly newsletter about everything happening in the business of entertainment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

There’s something ironic about Quentin Tarantino wanting to sell NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, related to one of his most important movies.

The director who bought the classic Vista Theatre in Los Feliz and adores 70-mm film projection also wants to sell digitally scanned pages of his handwritten “Pulp Fiction” script as crypto collectibles on a blockchain. Talk about intersecting plotlines!

Anyway, Miramax, the studio that released “Pulp Fiction” in 1994, is having none of it. The company sued the director last week, accusing Tarantino of breach of contract, copyright infringement and trademark infringement.

Miramax says Tarantino, who won an Oscar for writing “Pulp Fiction’s” screenplay, doesn’t have permission to sell the NFTs under the terms of his 1993 contract with the company and didn’t consult the studio before forging ahead. Tarantino’s lawyer Bryan Freedman says the filmmaker is allowed to sell the images under his “reserved rights.”

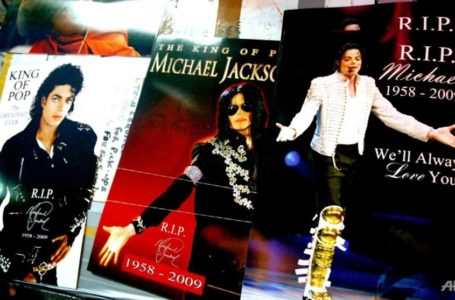

As a refresher, NFTs are basically certificates of authenticity that are tracked on a public ledger, giving people a reliable way to prove ownership of one-of-a-kind art, memorabilia and other items. But they’re not the artifacts themselves. An NFT is more like the deed than the house.

Tarantino earlier this month announced plans to sell NFTs containing “secret” content viewable only by the owner, including “the uncut first handwritten scripts of ‘Pulp Fiction’ and exclusive custom commentary from Tarantino, revealing secrets about the film and its creator.”

Although the dispute is fascinating, it may not turn out to be a landmark case for copyright and trademark law in the NFT age.

Aaron Moss, an intellectual property attorney at Greenberg Glusker who’s an expert in entertainment cases, wrote in a blog post that this wasn’t really much of a copyright dispute at all and didn’t even have all that much to do with the weird nature of NFTs. It’s more a matter of interpreting Tarantino’s contract.

“NFTs are clearly the bright shiny object that’s driving the parties to court and attracting public interest in the lawsuit,” Moss wrote. “But the less-shiny reality is that this is primarily a contract dispute — a fight about whether the publication rights Quentin Tarantino reserved in his agreement with Miramax include the right to sell digital screenplay scans.”

The case will hinge on whether the digital items attached to the NFTs fall under rights Tarantino retained in his deal with the studio, which include the soundtrack album, music publishing, live performance, print publication and interactive media rights. Crucially, the print publication rights in this case include “screenplay publication,” according to the contract language included with Miramax’s suit.

Under the terms of the contract covering “screenplay publication,” Tarantino can sell the “Pulp Fiction” script in book form or publish a making-of book or novelization, Moss said.

“The question,” he wrote, “is whether selling ‘1 of 1′ digital scans of pages from the screenplay falls within Tarantino’s publication rights or, conversely, constitutes the sale of something else, such as merchandise, that he assigned to Miramax.”

The dispute is really just a crypto-infused update of an age-old story: studios and artists battling to capitalize on famous work. Tarantino’s plan is another example of artists trying to use this increasingly popular type of asset to make money from existing work and promote themselves to a rabid audience.

But NFTs are a potential revenue stream for studios too, which have taken advantage of the boom by selling commemorative tokens tied to “The Matrix Resurrections,” “No Time to Die,” “Space Jam: A New Legacy” and “Ghostbusters: Afterlife.” That’s how NFTs of “Mini-Pufts” (or tiny Stay Puft marshmallow men) came into being.

Miramax isn’t the only company asserting rights amid the NFT craze. My colleague Matt Pearce in April wrote about how comic book publishers including DC were clamping down on illustratorstrying to sell digital superhero artwork as NFTs.

The Tarantino-Miramax could settle, like most entertainment lawsuits. The collectibles are expected to be sold next month, so there’s not much time for Miramax to make its next move, which would be to file a motion for preliminary injunction or apply for a temporary restraining order.

“I have a sneaking suspicion that Tarantino’s folks and Miramax’s folks will figure out a way where everyone can make money, because that’s the easiest path,” said Oklahoma City-based patent attorney T.J. Mantooth, who follows intellectual property cases.

It remains to be seen whether NFTs turn out to be the future of Hollywood collectibles or just another faddish hustle promoted by the financial gurus on TikTok. But these conflicts will certainly keep lawyers’ briefcases full.